Farmers standing in long queues to purchase urea fertiliser is an unusual sight in India. Yet, this has become a reality in several States this crop season, most visibly in Telangana. Officials explain that the good monsoon and consequent increase in the area under paddy cultivation have created a sudden demand.

But this explanation does not tell the full story. What is unfolding today is a direct result of the faulty crop price policy that successive governments have pursued for decades. Unless we connect fertilizer demand with crop pricing, we will continue to treat the symptom without addressing the root cause.

Before the Green Revolution of the mid-1960s, the use of chemical fertilizers was less than 2 kg/hectare in India. Farmers largely relied on organic manures. With the introduction of high-yielding varieties of paddy and wheat, alongside assured irrigation and fertilizer subsidies, urea use shot up dramatically.

In the early 1970s, total urea consumption was less than 2 million tonnes (mt), it had crossed 16 mt by 2010-11. Today (2023-24), India consumes over 21 mt annually, making it the second largest consumer of urea in the world.

State-level patterns mirror the cropping choices of farmers. Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and more recently Telangana, account for a disproportionately large share of urea consumption because of the dominance of paddy. Crops such as pulses, oilseeds and coarse cereals, which receive little price support, consume far less fertiliser. Thus, fertilizer demand has not been uniform; it has followed the trajectory of government procurement and price support policies.

Paddy vs other crops

Paddy cultivation is highly fertilizer-intensive. On average, farmers use 150-200 kg of urea per hectare on paddy, depending on the availability of irrigation. In contrast, pulses and oilseeds require far less, often less than 30-40 kg per hectare. Even wheat, though a major fertilizer-consuming crop, requires relatively less urea than paddy. This skewed pattern explains why a surge in paddy acreage immediately translates into soaring fertilizer demand.

In States like Telangana and Chhattisgarh, where paddy area has expanded rapidly in recent years due to attractive procurement at minimum support prices (MSP), urea sales have increased correspondingly. The present shortage in supply is, therefore, not simply a case of distribution inefficiency but of structural demand rooted in government policy.

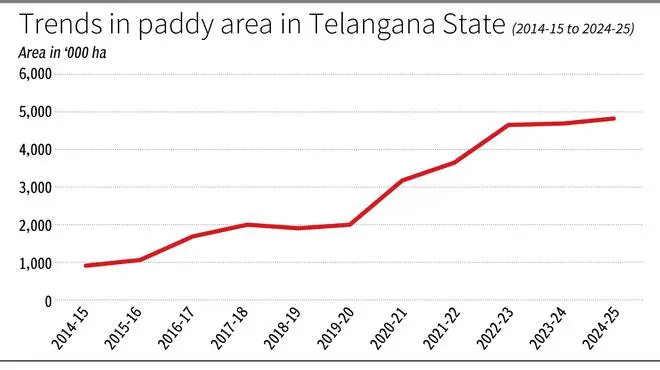

The MSP policy has strongly favoured paddy over other crops. While MSP is announced for 23 crops, in practice, large-scale procurement is effectively carried out only for paddy and wheat. Farmers in Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Punjab and Haryana know that if they grow paddy, the government will procure it at a guaranteed price. Such an assured market does not exist for pulses, oilseeds or millets. This price distortion has encouraged farmers to expand paddy cultivation far beyond agro-climatically suitable regions. Paddy was not grown before the 1970s in Punjab, but it is a dominant crop now. Similarly, Telangana, which traditionally cultivated cotton and coarse cereals, has witnessed its paddy area expand about five times in the last 10 years (Figure 1). As paddy expanded, so too did the demand for urea. The fertilizer queues we see today are a result of the MSP-driven bias in crop choice.

Farmers do use urea excessively and inefficiently, particularly in paddy cultivation. Several studies suggest that farmers often apply more nitrogen than recommended, believing that higher doses ensure better yields. However, the efficiency of nitrogen use in Indian agriculture is very low, estimated at only 30-35 per cent. This means that nearly two-thirds of the nitrogen applied is lost to the environment through evaporation, leaching/runoff.

But excessive use cannot be seen in isolation. Farmers’ choices are shaped by economic compulsions. With paddy assured of procurement and higher returns compared to other crops, farmers are willing to invest in fertilizers to maximise yields. Blaming farmers for “overuse” without acknowledging the policy-induced incentive structure is unfair.

The environmental consequences of excessive urea use are well documented. Continuous application of nitrogenous (N) fertilizers without adequate phosphates (P), potash (K) and organic manures has led to nutrient imbalances in soils. NPK fertilisers’ ratio should ideally be 4:2:1, but it was 11.6:4.6:1 in 2023-24. Many paddy-growing regions are now witnessing declining soil fertility and micro-nutrient deficiencies.

Excess nitrogen also contaminates groundwater with nitrates, posing health hazards. Runoff from paddy fields contributes to eutrophication of water bodies, damaging aquatic ecosystems. Nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide, is also released in significant quantities from over-fertilized soils. Thus, the ecological costs of cheap and abundant urea are enormous.

The root cause

The government has occasionally tried to control excessive fertilizer use through awareness campaigns, soil health cards or promoting balanced fertilization. While these efforts are valuable, they only scratch the surface. As long as policy incentives overwhelmingly promote paddy cultivation, farmers will continue to use large amounts of urea. The root cause lies in the MSP and procurement system that makes paddy attractive.

Therefore, as underlined by the Shanta Kumar Committee on “Reorienting the Role and Restructuring of the Food Corporation of India”, unless we diversify our crop procurement policies and extend real price support to pulses, oilseeds and millets, farmers will not voluntarily shift from paddy. Only when alternatives are made economically viable will the pressure on urea demand reduce sustainably. Without this structural reform, controlling urea use through regulation alone will remain ineffective.

To conclude, the long queues of farmers for urea are not just a supply chain problem; they are a reflection of our flawed agricultural policies. Urea demand in India has been shaped not merely by rainfall or technology, but by the skewed crop price policy that has privileged paddy over others.

Farmers use more urea not because they are ignorant, but because the system pushes them toward crops that demand it. The environmental costs of this pattern are already visible in declining soil fertility, polluted water and greenhouse gas emissions. The real solution lies not in rationing urea or blaming farmers, but in addressing the structural bias of procurement and pricing.

Diversifying support to other crops and rationalising fertilizer policies are the only long-term answers.

The writer is an Economist and former full-time Member (Official), Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal

Published on October 4, 2025