Rupee value against the US dollar is somewhat of a national obsession: the most tracked number in the Indian economic psyche, next only to the growth figures perhaps. On August 29, 2025, the rupee closed at 88.14 breaching the highly speculated 88-mark, and depreciated to 88.71 on September 24, 2025. With the breach, further conjectures around 90-mark reached a crescendo and added to the usual speculation of RBI’s intervention in the forex market to stall the rupee slide.

How does the rupee weakening impact us? And therefore, do we need to stall the rupee slide? There is no denying that for an import dependent nation like ours, rupee exchange value has a substantial impact through the import cost on essential commodities like fuel, fertilizers, iron and steel, and machinery and equipment. However, at this juncture of extreme trade uncertainty and keeping in view the long-term goals of rupee internationalisation, we argue it is time to let the rupee go.

First, how does the rupee depreciation impact the domestic economy? From the end-user perspective, a depreciation benefits the suppliers of currency (exporters, NRIs remitting currency) and adversely impact the buyers (importers, students or tourists). The importers of capital goods and raw materials are likely to adversely impacted, while exporters stand to gain crucial margins in the international market in terms of prices, and get more rupee for each dollar earned. However, both importers and exporters can hedge their foreign exchange exposures to avoid adverse impact on their businesses. In fact, as rupee internationalises, domestic firms must be encouraged to use instruments for hedging rather than expect a particular range in exchange rate.

Fuel import

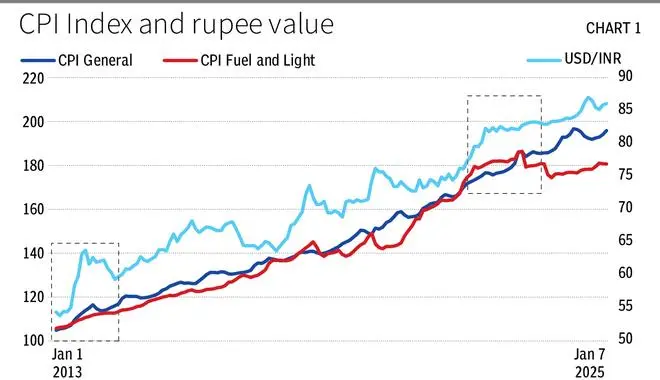

The other impact on domestic side comes from fuel import, which is the most substantial portion of our imports. Historically, of course, rupee depreciation has moved in tandem with higher crude import cost, seeping into higher inflation (Chart 1). Episodes like the 2013-rupee crash have made such grounding stronger. In fact, it was another August (28th) when rupee had breached the 68-mark, reaching 68.8 intraday. At that time a crucial factor contributing to the rupee slide was the high domestic inflation, sharp escalation in crude prices, and consequent higher domestic prices, feeding each other in a vicious cycle. Chart 1 plots monthly inflation with rupee value, and the longer run perspective tells us why the rupee has secularly depreciated.

Important to point out here that, while higher import cost does cause inflationary tendencies, the stronger causal relation is that of inflation and exchange rate of rupee. With a higher inflation, currency value invariably goes down: exchange rate is nothing but the value of our money against someone else’s currency (here the US dollar), so that a higher inflation, that eats into currency value, results in a depreciation. However, while rupee depreciation and inflation are intricately linked, this time around it is the trade uncertainty that is playing havoc. With inflation and crude prices both under control this time, rupee is fundamentally in a better condition than, say, in 2013.

Likely trajectory

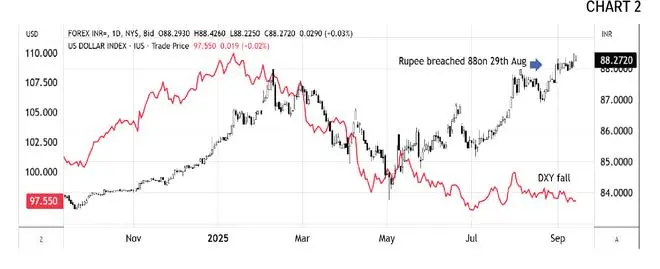

This brings us to the second question, what is the likely trajectory in rupee and should the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) try to stop the rupee depreciation? Chart 2 shows that in spite of dollar weakness the rupee has continued to depreciate. Further, after breaching the 87.99 on February 10, and 88 on August 29, the rupee is clearly on a further depreciating momentum, as suggested from indicators (lower panel). At this point, the fall in rupee seems to be justified by both fundamental and technical factors: thus, it may be temporarily possible to stall the fall, but we cannot stop it.

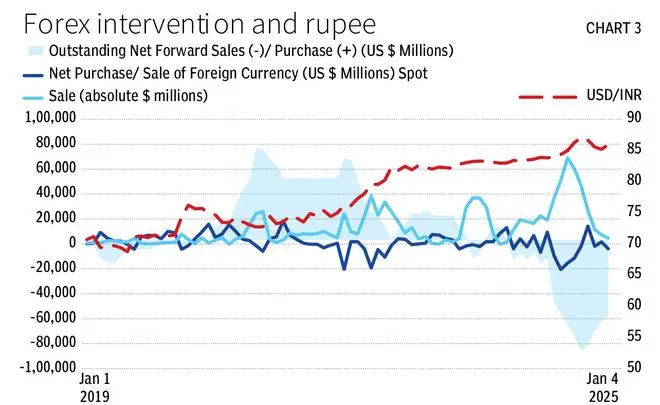

The Indian currency has seen consistent intervention by the RBI to prevent rupee volatility (Basu 2009, Das 2023): episodes like the 2013 depreciation saw the RBI intervening with a host of measures ranging from spot and forward dollar deals, policies like 80:20 and dollar swaps, etc. The intervention then worked in our favour and signalled a more stable currency in the face of domestic political uncertainty and high inflation.

Post pandemic while the Indian economy has been largely resilient, there was sharp inflation and consequent depreciation in 2022, brought about largely by global factors and some domestic supply side issues. Subsequently especially the period from 2022 to 2024 has seen consistent RBI interventions. In the August 2023 Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) statement, the RBI Governor stressed the fact that India has “adequate reserves” for forex “intervention” to curb “excessive volatility” (former RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das, August 2023).

However, the speculated RBI interventions to prevent sharp fluctuations helped the rupee to be in a narrow-traded zone: for example, while the period from September 2022 to September 2023 saw a range-bound movement from 80.45 to 83.26, the range narrowed from October 2023 to December 2023, staying between 82.75 to 83.48. In December, 2023, International Monetary Fund (IMF), in the annual Article IV country report for India, noted that from December 2022 to October 2023, the rupee-dollar rate “moved within a very narrow range”. In 2024, the rupee largely remained within 82.5 to 84, with a sharper movement coming during December 2024.

While forex market interventions led to stable exchange rates, it also has an impact on domestic liquidity conditions. As seen in Chart 3, there has been consistent interventions by the RBI in the last five years, with domestic interventions being supported by forward market interventions to avoid liquidity repercussions.

Leave it to the market

Yet there are at least three reasons why the rupee should be allowed to be market determined to the extent possible. Importantly, the RBI has constantly iterated that it intervenes only to avoid undue volatility.

First, the inflation situation is far better than in the past, and fear of imported inflation is less given the subdued crude prices in general and oil from Russia that India is currently purchasing.

Second, the weakened rupee would help exporters in dollar denominated products, given the heightened tariff woes.

Third, there is mixed econometric evidence globally on effectiveness of interventions in preventing volatility (Menkhoff, 2010, Naef, 2024). Studies from around the world, including that in India, suggest central banks have a difficult time trying to control the rate or volatility, especially when they are leaning against the wind (Chari, 2007, Roy Trivedi, 2020).

Fourth, for internationalisation of the rupee and the move to greater convertibility, we need to reduce the interventions in the forex market to the minimum. Encouragingly, news reports suggest the RBI has started diversifying its forex portfolio, reducing dollar exposure.

From a policy perspective, it is therefore recommended that intervention is minimised to crude price spikes which can impact domestic inflation. Attempts at rupee denominated crude price purchases should continue to reduce dollar dependence with dollar reserves earmarked for the same, along with oil swaps. Exporters can be supported to navigate choppy trade waters, by extension of credit cycle and further digitalisation of trade process. Currency can be helped with greater exports, and that can come only when the exporters are competitive in the global markets, and can move up the value chain.

The narrative for the rupee should change now with greater confidence that the inherent strength of the Indian economy will drive the currency value, as we allow for greater independence for the currency.

Trivedi is Associate Professor, National Institute of Bank Management, and Das is ICICI Bank Chair Professor, IIM Ahmedabad. Views are personal

Published on September 24, 2025