Companies want to deep sea mine — even without a rulebook : NPR

March 27, 2025 | by ltcinsuranceshopper

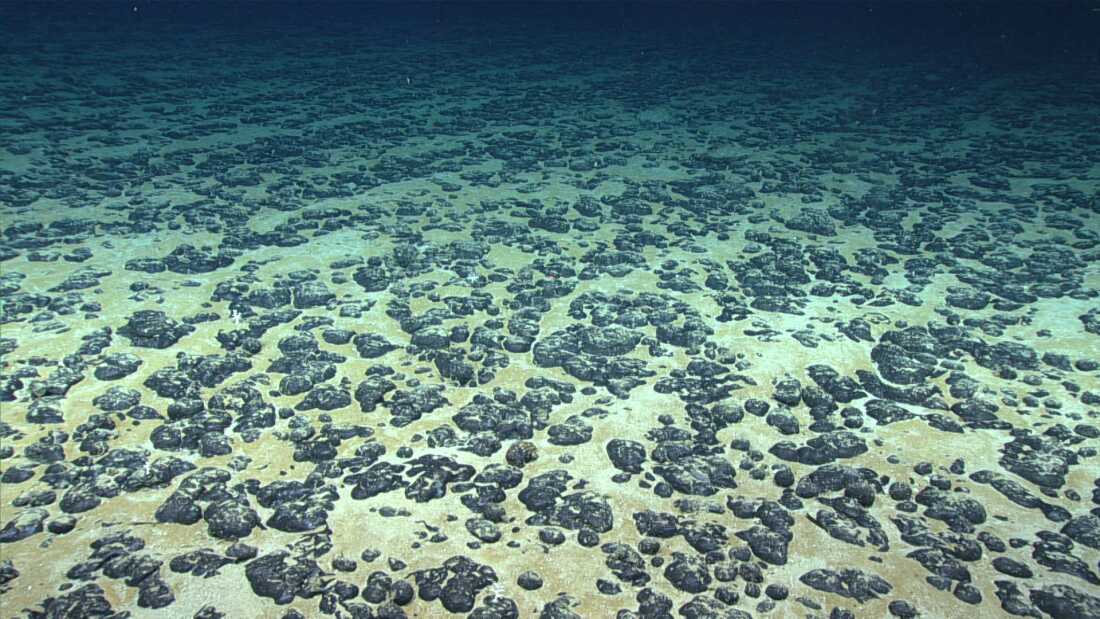

Negotiators are hammering out rules to govern mining on the ocean floor, where critical metals are found in deposits called polymetallic nodules. Here, ferromanganese nodules in the North Atlantic.

NOAA Ocean Exploration

hide caption

toggle caption

NOAA Ocean Exploration

In the global race for critical minerals, one little-known international agency holds the keys to a potential motherlode: vast quantities of metals located on the remote seafloor.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has worked for more than a decade to draw up regulations for a future deep-sea mining industry. Negotiators say the process could take years more to complete.

Now, though, one mining firm says it plans to move forward — with or without a rulebook in place.

The Metals Company, a startup based in Vancouver, British Columbia, claims it’s ready to launch the world’s first deep-sea mine in the eastern Pacific Ocean. That poses a challenge for ISA negotiators meeting this week in Kingston, Jamaica.

Experts say the outcome could reshape the mineral economy, with profound impacts on marine ecosystems.

“We’re deeply concerned that mining could go forward absent regulations,” said Liz Karan, director of ocean governance at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “That would have potentially disastrous consequences for ocean health.”

Why mine the ocean floor?

Scientists know little about the deep seabed. Most of the ocean floor hasn’t been mapped. Researchers believe most species living there remain unidentified. But one thing is certain: There’s a lot of metal down there, including key materials used in technology like electric car batteries.

The U.S. Geological Survey has estimated that a single swath of the Eastern Pacific, known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone, contains more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all combined terrestrial reserves. These metals (plus copper) are bound up in potato-shaped deposits called polymetallic nodules, which form over millions of years as minerals in the seawater accrete around bits of organic matter. Those nodules are scattered by the trillion across the sandy seabed of the Clarion Clipperton Zone, an area about half the size of the contiguous U.S. that sits between Hawaii and Mexico.

Those nodules have tempted would-be miners for decades. Mining firms claim the deep seabed could provide a major new source of minerals independent of China, which controls the supply of many critical minerals.

A Vancouver-based startup, The Metals Company, says it’s ready to launch the world’s first deep-sea mine in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Here, researcher Andrew K. Sweetman explains how samples are obtained during a 2021 study on mining’s potential environmental impacts.

Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

How would deep-sea mining work?

To retrieve the nodules, mining firms plan to send uncrewed collector vehicles down to the bottom of the ocean. The Metals Company vehicle, which is about the size of a school bus, would crawl along the seabed, hoovering up nodules and sending them through a miles-long vertical tube to a ship waiting on the surface. (Some observers describe this system as the world’s longest vacuum cleaner — but for critical minerals instead of dust bunnies.)

In 2022, The Metals Company completed a field test of this system in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, which the firm deemed successful. Now, the company wants permission to begin commercial production.

The Metals Company says it will apply for a mining exploitation permit from the ISA on June 27, whether regulations are finalized or not.

What are the environmental impacts?

Nobody knows for sure, since deep-sea mining has never been done at commercial scale.

Supporters of seabed mining claim it will be less destructive than mining on land.

Gerard Barron, CEO of The Metals Company, points to Indonesia, the world’s leading nickel producer, where mining happens in biodiverse rainforest regions. In contrast, he argues, the vast, sandy plains of the deep seabed harbor far less life.

“For some reason, people think it’s OK to go digging up rainforests to get the metals underneath them, yet we’re debating whether we should be going to pick up these rocks that sit on the abyssal plain? Something has got screwed up here,” Barron said in an interview with NPR.

Many marine scientists and policymakers disagree.

Researchers say they’ve identified more than a dozen ways seabed mining could damage ocean ecosystems. Animals including sea sponges and anemones grow on the nodules, so removing nodules would destroy that habitat. Sediment plumes released from mining operations may harm creatures adapted to the clear waters of the deep ocean. Noise pollution from seabed mining could interfere with animal navigation and communication.

Polymetallic nodules containing certain critical minerals can be found scattered across the seabed in some parts of the ocean. Here, manganese nodules found off the Southeastern U.S. in 2019.

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

hide caption

toggle caption

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Hundreds of researchers have called for a pause on deep-sea mining until scientists learn more, which could take years. Some companies — including automakers and tech firms like BMW, Volkswagen, Volvo, Google and Samsung — have pledged not to use seabed minerals.

Some mining companies say damage could be mitigated with new technology. One startup, Impossible Metals, is developing a fleet of underwater robots that would hover above the seabed, instead of crawling along it. The robots would use mechanical arms to pluck nodules that have no visible life on them. The company claims this method would eliminate sediment plumes and reduce noise pollution, though the technique hasn’t been tested at the extreme depths where mining would occur.

Who decides if mining happens?

Individual countries regulate mining within their Exclusive Economic Zones, generally extending 200 miles from the coast. A handful have begun permitting the exploration for seafloor minerals, including Japan, the Cook Islands, Papua New Guinea and Norway (though Norway paused its permitting process late last year).

But most of the seabed lies beneath the High Seas, beyond the control of any country. That’s where the ISA has jurisdiction.

The ISA was launched in 1994 by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a treaty colloquially dubbed the Constitution for the Oceans. It includes every major economy with a coastline except the United States, which never ratified the treaty.

Polymetallic nodules, like this manganese nodule, form over millions of years as minerals in the seawater accrete around bits of organic matter.

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

hide caption

toggle caption

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

The ISA has granted 31 contracts allowing member countries (and partnered companies) to explore for seabed minerals, mostly in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. China has snapped up five of these exploration contracts — more than any other country.

But nobody has moved from exploration to exploitation. That’s in part because the ISA hasn’t finalized regulations for commercial-scale extraction. ISA negotiators have spent more than a decade drafting a mining rulebook, which will cover everything from environmental rules to royalty payments.

ISA countries set a goal of finalizing the regulations this year. But key issues in the draft rulebook remain unresolved as negotiators meet this week to hammer out the details at ISA headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica. The ISA appears unlikely to complete the regulations this year — let alone by June 27, when The Metals Company plans to submit its mining application.

About three dozen ISA countries have called for a precautionary pause on mining activity, at least until rules are complete. Other countries have resisted those calls, including the Pacific island nation of Nauru, which is partnering with The Metals Company on its mining project.

What could happen next?

While the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea says companies can apply to mine before regulations are complete, it doesn’t specify exactly how the ISA should evaluate such applications.

“This is unknown territory,” said Karan. “This isn’t something that the ISA has a clear roadmap for.”

The ISA could simply reject The Metals Company’s application out of hand. Or it could provisionally approve the application, likely with some strings attached, then revisit the matter once regulations are finalized. Either approach could spark legal disputes before an international tribunal.

A third possibility is that The Metals Company chooses to forge ahead outside the ISA legal framework altogether — a possibility that irks experts like Karan.

“I’m deeply concerned with the prospect of unsanctioned mining taking place in areas beyond national jurisdiction,” she said. “That would be contrary to international law.”

The Metals Company CEO Gerard Barron said “nothing is off the table.” He noted that the United States isn’t bound by ISA rules. Companies eager to begin extraction could theoretically do so, by partnering with a U.S. government unrestrained by global seabed mining law.

“The international community has an opportunity to put these rules in place. But if they don’t, it doesn’t mean this industry will not move forward,” Barron said. “One way or another, this resource is going to be developed.”

Travel for this reporting was supported by a grant from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.

RELATED POSTS

View all