With its pungence and unmistakable aroma, the onion dictates far more than the taste of a curry. It decides the fate of farmers, shapes the promises of politicians, and fuels the inflationary fire of the Indian economy. At the centre of this saga stands Lasalgaon in Maharashtra’s Nashik district, home to Asia’s largest onion market. Here, fortunes rise and fall with every sack of bulbs.

This month, once again onions have sparked unrest. Farmers allege that, ahead of the Bihar Assembly elections, the Union government is releasing buffer onion stocks to push down prices. For growers who had carefully stored their harvest in makeshift warehouses — locally called chawls — waiting for better rates, the strategy is devastating. The onions are rotting, and if brought to market, they fetch only a fraction of expected prices.

This is not a new story. Onions, harvested in both kharif and rabi seasons, dominate India’s agri-politics. Rabi onions, which make up nearly 70 per cent of the annual production, are harvested in March and can be stored for months if conditions are right. But storage is a gamble: The bulbs last only two-three months in regular environments, and slightly longer if humidity is controlled. When onions rot, the consequences ripple from Lasalgaon to Delhi, triggering consumer protests, farmer agitations, and policy manoeuvres.

India, the world’s second-largest onion producer after China, accounts for more than a third of global supplies. In 2023–24, Maharashtra led production with over 35 per cent of the country’s produce, followed by Madhya Pradesh at 17 per cent. Karnataka, Gujarat, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Telangana round off the list. Despite being an agricultural powerhouse, farmers routinely battle the same old nemesis: Onions going waste in storage, leaving growers with crippling losses.

Kalyani Shinde found a solution for farmers’ pain points

A Childhood in Lasalgaon

For one young woman, the story is deeply personal.

Growing up in Lasalgaon, Kalyani Shinde lived amid the rhythms of the onion trade and cultivation. Almost every relative in her extended family was linked to the ecosystem in some way. As a child, she often overheard conversations about prices, market swings, and, inevitably, losses.

By the time she was finishing her computer engineering degree at Amrutvahini College of Engineering in Sangamner (in Maharashtra) in 2018, she once again heard the familiar lament: Stored onions were sprouting, decaying, and unsellable. Her own family expected her to complete her degree and move to a city for a job. But the constant echo of the farmers’ woes made her pause. “I remember 2016-17 was a bad year for farmers,” she recalls. “I thought, why shouldn’t I try to solve this problem? After all, I was one of them.”

Until then, entrepreneurship was a word she hadn’t even heard. But the problem — onions rotting in storage — was real and urgent. She began brainstorming. Moisture loss, fungal infection, sprouting, decay — each factor contributed to post-harvest losses. Could technology intervene?

A Spark of Innovation

.

Her initial idea was to design “smart warehouses” for onions. She visited farmers and inspected traditional storage structures made of bamboo and iron mesh. But she quickly realised that farmers would reject costly infrastructure changes. The crux of the problem was detection. Farmers only discovered rotting onions when large portions of that stock had already spoiled — usually identified through odour, a late and unreliable indicator. Worse, onion waste is contagious: once it begins, it spreads quickly, turning piles of produce into losses.

Kalyani Shinde applied to Digital Impact Square, a TCS Foundation initiative in Nashik. Selected as an innovator in 2018, she embarked on a journey that would transform her from a computer engineer into an agri-innovato

“If we could detect the waste in its early stages, farmers could save most of their crop,” Shinde reasoned. That was the problem statement she set out to solve.

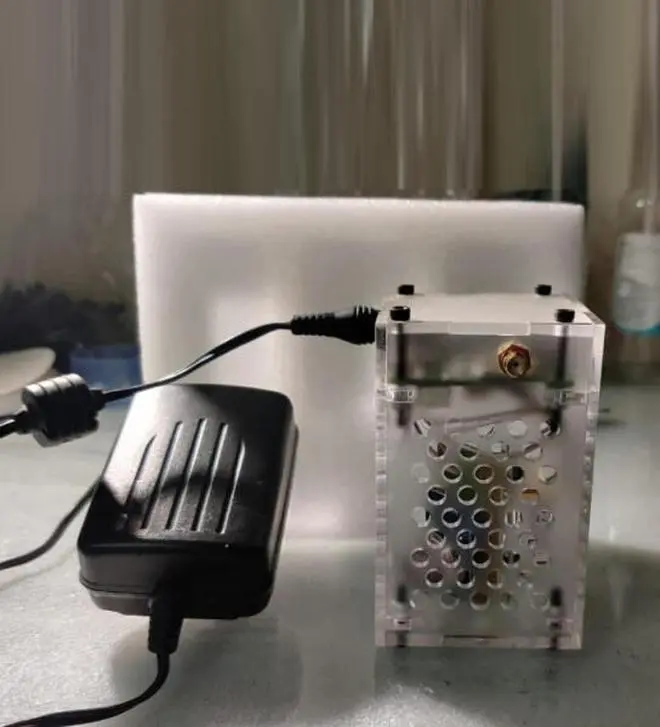

The solution she imagined was an IoT-based device capable of monitoring the warehouse environment and identifying spoilage early. It would take her three years of research, trial, and error to build a working prototype.

Building Godaam Innovations

The result was Godaam Innovations, India’s first IoT-based onion storage solution — a patented device that monitors the microclimate of warehouses. Godaam means warehouse in Hindi, and Shinde says she chose the name because she wanted it to be simple and for easy recall.

The technology tracks temperature, humidity, and gases emitted during the early stages of spoilage. The hardware includes four-five sensors placed across different compartments of a warehouse. These sensors continuously collect data on environmental parameters and transmit them to a central Wi-Fi router. The information is then sent to a server where algorithms run in real time.

“We can identify waste as early as one-two per cent,” Shinde explains. “That’s enough to stop further damage. Once farmers get an alert, they can grade their crop and sell the affected compartment before the rot spreads.”

This innovation was more than just a gadget. It was a bridge between farmers and technology, between traditional agriculture and data-driven decision-making.

By 2023, after years of pilots, Godaam Innovations was commercialised. Today, more than 800 devices are in use across India. The company operates on two models: Direct sales at ₹15,000 plus GST per device, or rent at ₹150 per tonne per month.

The target audience has shifted from individual farmers to Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), retail chains, exporters, and warehouses with capacities of over 200 tonnes. Recently, the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation (NAFED) purchased 300 devices and services for two years — a milestone project expected to expand further.

The device that identifies spoilage early

How Godaam Works

The process begins right from sowing. Farmers are onboarded, and data collected through the crop cycle until harvest. Before storage, warehouses must be prepared with compartments and bottom ventilation. Once onions are stacked, the IoT device is installed to monitor conditions round the clock.

Real-time alerts are sent to farmers in their local language, empowering them to make timely decisions. The system not only reduces wastage but also builds trust in storage infrastructure, making it possible to stabilise supply for domestic and export markets.

Vijay Patil, a farmer from Deola in Nashik, has installed the device in his 80-tonne onion storage facility. He says the sensors alert him at the very first sign of onion rotting. “This has saved me from huge financial losses and helped me make better decisions about when to take my produce to the market,” he explains. Patil adds that all onion farmers should adopt this technology, as every measure to reduce losses is crucial for their survival.

The company is also exploring diversification. Poultry and grain storage are potential new frontiers for the technology.

Breaking Barriers

Shinde’s journey was never just about technology; it was also about breaking social and gender barriers.

Her parents — neither graduates — had hoped their daughter would secure a stable job. When she chose agriculture instead, relatives scoffed: Why spend years studying engineering only to return to the farm? Yet, her parents stood by her, even as she promised never to ask them for money or take a loan.

In 2021, when her work was featured in the media, perceptions began to change. “My parents saw the publicity and felt I was on the right track,” she says.

But gender bias lingered. In agriculture’s male-dominated ecosystem, she was often the only woman in the room. At one Maharashtra State Agriculture Board meeting in Pune, she sat quietly while 25 men — officials and marketing chiefs — conversed among themselves. Only when the head introduced her did the tone change. After her presentation, fifteen officials lined up to speak with her.

“It is up to you,” she reflects. “The work talks for you. Gender matters, but it doesn’t matter. People may judge you, but your work can change the conversation.”

Her presence challenges entrenched norms. A few years ago, Lasalgaon’s market erupted in chaos when women attempted to trade onions directly. Though many licences were in women’s names, the businesses were typically run by men. Women were unwelcome. Yet, over time, female farmers forced open that space. Now, Shinde has breached another bastion — not as a trader, but as an innovator ensuring those onions survive long enough to be sold.

Scaling the Future

Today, Godaam Innovations is focused on scaling beyond Maharashtra, with plans to expand to Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Karnataka. The company is also building a warehouse management platform to connect buyers and sellers directly.

Shinde remains grounded. She remembers her first field visit, where she assumed farmers would lack technological exposure, only to meet one carrying an iPhone. “Don’t go with pre-assumptions,” she advises. “Go open-minded to understand the problem.”

Her story embodies the larger struggle of India’s onion economy: Resilience, adaptation, and the search for stability in the face of volatility.

The Onion and the Nation

The saga of onions is not just about farmers or traders. It is about India’s food security, rural livelihoods, and political calculus. Prices spike between October and December, the lean season, and can decide electoral fortunes. Policymakers walk a tightrope between consumer anger over inflation and farmer protests over low returns. In this battlefield, every innovation counts. By reducing wastage, stabilising supply, and offering farmers a fighting chance, Godaam Innovations adds a new layer to the onion’s long and teary story. From Lasalgaon’s fields to warehouses across the country, the battle continues. But thanks to one young woman who refused to look away, the pungent bulb may finally have a smarter, longer life.

Published on September 29, 2025